There is no king who has not had a slave among his ancestors, and no slave who has not had a king among his. -Helen Keller

In the woods by the small Dunker Church they had ended up stranded and unconnected. The line that they had moved with, out through the dewy fields of that early September morning, it had been hacked at hard by the enemy. Wavering and loosening, the regiment had somehow gathered the kind of steam not necessarily desired in the midst of battle. But that is the way these things sometimes come down. We can close our eyes and try to see the now: Union boys, slathered in the thick of it/ steaming like a piqued bull/ working with the unnatural swiftness of some sidewinder snake out there in the slick grass. The whole horrifying scene a concurrent face full of everything at once. More than we can ever know.

Oh, my man:

The chaos in the acrid smoke.

The hollering of unseen men not far away.

The whistling of the balls and the unnerving POOM… POOM… POOM… of the big guns opening back in the farm lots to your rear. Other guns starting in from way out in your front somewhere, and they drop their heat down in your crowd. Taking bones and twisting them out of the skin of a man. Showing his insides, pinching his face into the kind of tight disbelief that comes with a sudden kind of death. Chips of brain on your coat, glistening violet slugs that appear in dark magical puffs, and holding your breath is all you can do/ all I can do/ but damn, what I would give to run out of this whole mess now. To hell with the cause. To hell with any of it. Who wants to die this morning? Not me.

Not us, I’m figuring.

Ah, but you see: sweet impetuosity rules the day. Thus what had begun, well, it had to play out, didn’t it? And so the madness of the moment had swept them up and there was no turning back at that point. On that Maryland field that morning, like so many fields past and so many still yet to come, even to drop down and play dead wouldn’t have likely saved your soldier. Something at some point would probably have slammed into him and it’s all too much to understand. Still, I mean, some errant shell hammering the earth a few feet from his skull, sending the farmer’s dirt into his brains and spilling his brains out onto the land. Or some panicked colonel’s freaking out horse bashing a hoof right through this balled-up fellow’s temple. The din of war silence so we can hear, just for an instant, the lonesome sound of the faint crackling of a Pennsylvania kid’s head popping open.

_____

Sigh.

I don’t know.

How the hell do I know?

How the hell does anyone?

The flashes of consciousness/ the scent of total fear/ the taste of plunging into certain mortal pools/ the all-encompassing totality of being a Civil War soldier in a Civil Battle once upon a time/ it would all come and go rather quickly, I imagine, and yet would remain for each survivor- in dream and in nightmare- for the rest of their lives.

Some would attempt to drink it away. Others would beat it with a vengeance into the puffed ears of their tired wives or into the clenched jaws of their still young, weak sons. Many would tuck it down into their macho chests and march around like real men of the town, all civil and respected.

But nevertheless, for the Antietam boys, it surely remained.

The memory of that morning.

And for the men of the 125th Pennsylvania who survived Antietam, they were probably always trapped out next to the woods by the little country church. Standing in the church or walking down the lane/ eating a ham sandwich in a tavern or trying to take an outhouse piss on a dark cold Christmas morning beneath a sprawling cathedral ceiling of stars/ standing there all alone, one more time, and sensing it all again: the crashing down storm of the energy fear. The metallic taste of a single moment from the past/ when clarity had happened in the middle of fog/ before any help had caught up. That understanding then, that the goddamn Rebels were closing in on their front, and then on their flank, and by the time one soldier realized it all the men around him were doomed. Old friends taking lead in the eye or in the side of the neck. Or in the groin, with a scream, down he went, the blood flowing purple as it slipped down below the surface of all that campfire coffee and all of those letters home.

Like wasps, the shots hissed by and I try to fathom that particular moment but I never really can. No one can. No one will ever know any of it for sure again. These days the old Civil War is merely a strangely comfortable daydream for all of us who ponder it but never knew it at all. An era, true, but more than that is lost, I’d say. With the passing of time we lose the people. And with the passing of the people, we lose the acorns rolling around in our palms/ the old fingers pointing at the sky/ a series of a hundred trillion minuscule moments that together told the only possible tale, they all faded away into basic oblivion when the last veteran took his last breath and died.

Son of a bitch.

It isn’t fair.

Then again, it’s kind of beautiful, ain’t it? The ownership of the shots and the scared and the shaking and the hissing and the pissing in their pants and the vulgarity of the horrifying instants with the bone chips and the intestines on the dirt/ and the crying farm boy with no arm standing there in the smoke/ smiling for a second/ then melting into memory like pines on fire. He knew what he saw, the old soldier did. He knew what he fuck he saw that morning.

But now, it goes. The last Antietam fellow is vacant rattling breath, his back on the bed, cloudy eyes failing to focus. His one granddaughter trying hard, putting a little water on his old chappy lips, but it just runs down his cheek, fresh narrow streams flooding down the ancient hillsides, trickling down his gray stubbly chin and pooling up in shallow puddles in the folds of his wrinkled neck.

Cool well water heading down into the collar of his oniony night shirt as he drags the hazy battle off the surface of this planet once and for all.

_____

_____

At times, and I still can’t believe any of this, but at times when I lay down on the bed, on top of the blankets, my work boots dirty with cut grass clippings and flecks of dog shit or whatever other stuff I’ve been moving through out there in the world (but I plop them up anyways), I stare into the ceiling tiles and I tell myself that her people were there. Her 3x great grandfather, Private David Deviney (or Devinney, depending on which way the old winds blew), he was there.

There as in he fought at the Battle of Antietam/ the ‘Bloodiest Single Day in American History’, where 23,000 men were killed or wounded on that rural Maryland ground across just one September’s day. Private David Porter Deviney, 22 years old, 125th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, Company I.

He was there. And you know what? If you ask me, then that means she was there too. At least in my mind it does. In a strange but obvious way.

Ha.

How beautiful is that?

Arle at Antietam.

In the mystical way, hoss.

In the ways of new blood stretching back.

_____

Mother of god, I remember thinking to myself.

Mother of god, I remember saying out loud.

Antietam.

Mother of fucking god.

He was there. He was there. He was there.

The mad adventure of a young man’s lifetime. The relentless marching of war. The loneliness and the struggle. The lingering deep blues and the flash fire memories that remained forever hard to process. The death. So much death. So much terror. So much boredom. So much homesickness. Hardly ever any women. Hardly ever any kisses. Years going without. Years walking into the end. Or not. You could never be sure.

So many questions.

Hardly any answers.

A glimpse of grand generals.

The beating down sun.

Old newspapers smeared with other soldier’s sweat.

The Emancipation Proclamation whispered on a wind.

Hard tack dipped in hot bitter coffee.

Tiny delicate snowflakes on the face of a stiff dead horse.

Whiskey numb Christmas Eve lips.

Guns going off in your ear.

In the night.

In your dreams.

And in the morning.

In your face.

Arle and her grandfather.

They were there.

There, they were.

_____

_____

A few years ago, in a small Franklin County, Pennsylvania graveyard, me and Arle moved slowly through the old stones, Sheetz coffees in our hands, reading all the names of the goners, trying to find Deviney’s. We were looking for his name in particular, but we had to come to appreciate these searches, to get off on the build up and even the possibility of disappointment. With the advent of Covid and the brave new world that it had fostered, we’d gravitated towards cemeteries as casual entertainment, digging deep into our new Ancestry.com account with a newfound fascination for our unknown past.

That Saturday morning was early summer, and there was sunshine and blue skies and we were happy to be together. To be alive there on top of the dead. We had talked to an old military guy who was there to bury his father. He had been parked there when we pulled to the side of the road in this tiny country town. I don’t remember how we ended up speaking to one another but we did. He had a southern accent. He told us he had been born there in the town of Concord but had joined the army long ago and lived in the south for many, many years. His eyes were wet, like he’d been crying. Or I thought maybe he was half in the bag, but that’s just how I tend to think.

A man is weeping because he is sad or is he tearful because he is damn drunk?

At one point in the friendly conversation, I am getting the feeling that he hadn’t seen his recently deceased dad in a long, long time. We talk about the small town we are all standing in and we mention that we are there in hopes of tracking down an old soldier ourselves.

We say his name. We mention David Deviney and this guy, he stops us in our tracks, me and Arle, when he says to us that he thinks he knows where that family lived. I feel my spine spinning/ electricity shifting out into all of my veins and muscles and nerves. I am hopeful. So is Arle.

Then he tells us.

“Over there,” he claims, matter-of-factly, as he points at a lot just across this street from the cemetery. “I seem to remember the whole family living in a farm house right over there.”

I look at Arle.

She looks at the man.

I look at the lot. There’s a rancher on it now, far too new to have dated back that long. But still. This is a very old rural town and so there must have been a farmhouse or some kind of dwelling there way back when Deviney roamed these country lanes.

The grieving man, he is short with a crew cut and his eye rims are pink and I watch him as he looks at the place where he says Arle’s people once lived. Then his gaze wanders, out beyond this place that may or may not hold any significance to us, out across the rising fields to where the woods begin at the base of the steep ridges at the edge of all of this. For a few scattered random seconds I daydream of him walking up there when he was just a slingshot country boy with a burlap sack filled with tiny stones and a piece of cheese and maybe a few slices of raw onion wrapped in some cloth. Some fuel for the climb. A couple cigs. A short busted knife in an oversized dirty leather sheath. Then I see him/ and I kind of stand with him/ up there on the mountain, looking down at the town. Looking down at his Dad hammering a piece of wood in the old backyard. The bap bap bap of this long forgotten hammering trailing his steady arm raising and falling by a millisecond with each blow. And in each of those misaligned echoey instants/ as the glitching pounding reaches the boy behind the ancient beat/ he looks down on his father, down on his world/ and he somehow knows that nothing will ever quite add up here.

I slug a shot of my coffee and coast back down to the graveyard.

Like a wild turkey.

Like The Angel of Death.

Then I end the talk so we can look for the goddamn grave already. I think about standing with the man as they say the final words by the hole in the ground near his Dad in the box, but it feels weird. Later, I watch him standing there, just him and a stranger who showed up in a military uniform. He’s obligatory, I think. Part of the package for being a soldier once upon a time is that they will send a soldier to see you off. Or two soldiers, I guess. The required stranger and the guy’s one son. And the preacher who probably didn’t know the dead man or his son.

No one else comes.

It’s awkward.

I selfishly wanted this place all to ourselves.

I stumble around staring at my phone/ sucking down coffee/ looking at where Arle’s grandfather is supposed to be. But we never find his name. We find his wife’s name, but not his. I don’t get it. I don’t understand.

It pisses me off. I feel lost/ unmoored/ adrift/ deeply unsatisfied. He must be down there somewhere. Pappy Deviney. Private Deviney.

He was at Antietam.

I bite into my lip and try to hide what lives inside me.

I want to find him so bad though.

I want to connect with what I can never connect with.

Between you and me, dude, I want to fucking dig him up.

_____

_____

We tell ourselves stories in order to live. -Joan Didion

_____

There is a monument to the 125th Pennsylvania out past the Dunker Church not far from the Visitor’s Center at Antietam National Battlefield. We went there once, Arle and me. It was cold, February, a few weeks before the virus plague came along and shut the world down. The old times, I guess you could say. We were there in the Old Times.

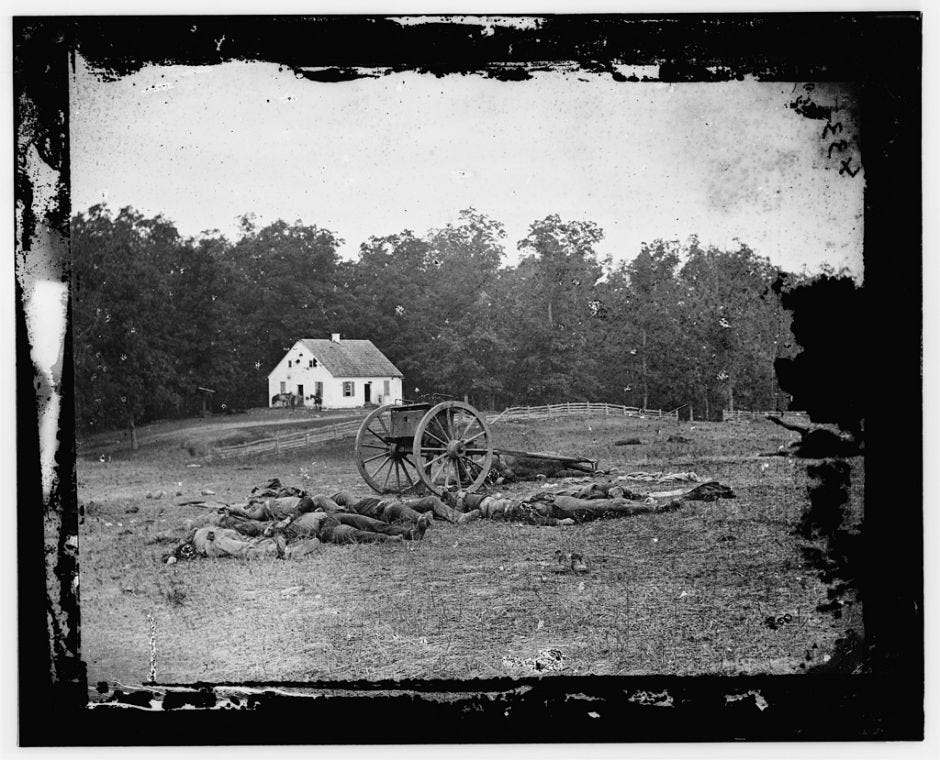

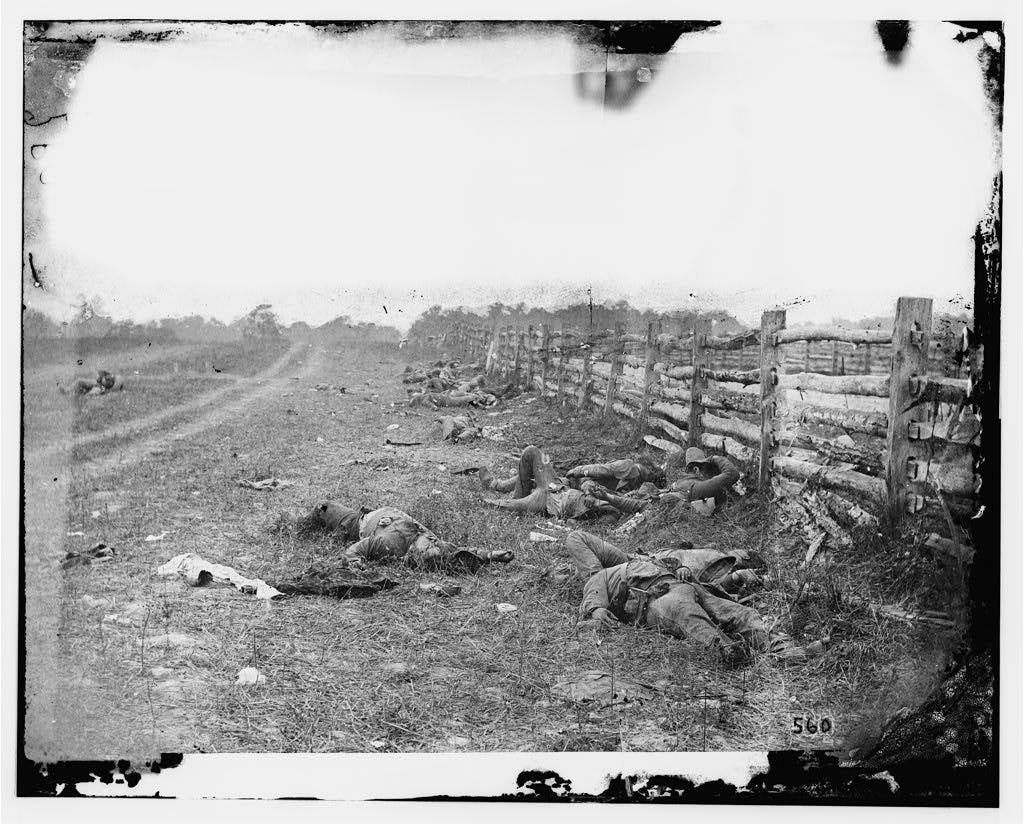

The land is flattish, with slightly rolling hills at places that you wouldn’t even notice from a car on the paved roads, but which become apparent as a player in the battle when you walk along by foot. Gentle swells and rises played a major role in the battle that day. There are photographs, some of the first ever taken of a battlefield just after the fight, in which the legendary 19th century photographer, Alexander Gardner, captured something that had, up until that point, never been captured before.

In the images, we see the dead.

They haven’t been that way long though. Just days before, they were marching. They were sons and husbands. They held food in their fingers and blinked into the sun.

Gardner captured them in their new role though, as fallen fighters, their lives run out, their bodies bloated in farm lanes, sprawled out and looking stiff near blown up horses down in the mud. The photos smell of decay. They reek of a nauseating miasma. They burn without burning and we stare at them, even today, with a macabre fascination.

I turn them upside down. I try to look into the gaping mouths of certain soldiers.

Did they die screaming?

Did they die cursing?

Did they know they were dying as they fell?

Or did they lay there dying for a long time/ across a night and a day/ undiscovered/ unaided/ unsure what the hell was happening/ in and out of consciousness/ overwhelming pain in their bones/ in their guts/ blood drawing flies and flies shitting in the open gashes where the bones could be seen like little elephant tusks in the strawberry pie.

The wind was so cold that day we walked out there to see the monument. Winter days, late in the afternoon, are good times to walk battlefields. There’s no one else around. People don’t need that shit. They don’t want to deal with locomotive blasts of February charging through their North Face shit and lashing into their skin like grape shot. People want the battlefield to be enjoyable. They want good food nearby. They look at the monuments and pretend to be riveted but really they are thinking about a Bacon Deluxe at Burger King and maybe a chocolate shake or maybe a pale ale in a nice little microbrew place with a cosy fireplace and good nachos.

I kept wondering if Arle was thinking that stuff. But I think she wasn’t. When we got there to the exact spot where her grandfather had once stood, out beyond the church, in the face of the approaching Rebel Army, I could tell she was feeling it hard.

I let the wind stab my face.

I listened to Arle sniffling through the frozen blasts pushing through her.

There are no leaves on a lot of the trees in the winter, of course, so the battlefield where Private Deviney and his fellow 125th soldiers made their stand that day appears more haunted and more desolate. A pine forest at the West Woods stands firm though. It quivers in the wind, like a wavering line unsure of its own fate. I watch Arle looking up at the soldier on the monument and I imagine she is wondering what her ancestor was thinking or feeling on that morning so long ago. He was young. He was only enlisted for a 9-month term of service. The whole regiment was. But what does that even mean when you are running towards the sound of your enemy’s volleys?

Are you scared shitless?

Are you brave beyond explanation?

Do you hide behind another soldier when all Hell breaks loose?

Do you hear the thud of him taking one in the chest?

Did you save yourself and watch him die?

Do you even admit that shit or do you hold it close forever?

After the war, years later, the 125th PA regiment will gather at the Dunker Church on the morning after a reunion banquet in the nearby town of Sharpsburg. There are a lot of men present but not all of them. Many had died by then. Others were likely living lives that disallowed them to travel to Maryland to be a part of it all.

Some probably simply didn’t want to attend. Maybe they spent their whole lives trying to forget the whole goddamn war, you know? Maybe they didn’t want to pretend that they gave a rat’s ass about any of their old comrades. Maybe they resented each and every one of them/ saw them as aging reminders of a hard terrible time when the glory they all talk about now was revealed as a lie or a sham.

Maybe certain soldiers were halfway to the battlefield when they got off the train and walked into the station and bought a whiskey and then boarded a train back the way they came from. Headed home. Never to see it through, this return to the battlefield.

Maybe some of the men who showed up were sorry that they did.

It’s impossible to know, huh?

In that photo there are a lot of faces but we don’t know if Private Deviney was among them. I have never been able to prove he was. Or that he wasn’t.

Arle and I walk over to that spot after we traipse all over the cold ground that afternoon. We stand where the old soldiers stood for certain once. We know it from the picture of the reunion.

I watch her peering into the church through a side window.

I think to myself that the Civil War is one of the greatest things that has ever happened to me. To us. To anyone who has ever lived.

But then again, that’s bullshit, too, and I know it.

We are going to eat Mexican food and drink wine and beer in nearby Shepherdstown tonight.

And the Civil War is a billion miles away.

_____

_____

Sometimes I am two people. Johnny is the nice one. Cash causes all the trouble. They fight.

-Johnny Cash

_____

In the years just before the South seceded and things went the way they did, young David Deviney was in trouble. It was a pattern that he would continue stitching across the decades to come too. Although the war was the focal point that brought Arle looking for him, with me in excitable tow. A Civil War soldier’s life, if he somehow survived the enemy and the disease, pisses all over our concentrated efforts to see it as one thing and one thing only.

The war, for many, was simply a chapter. The magic chapter, I always thought. The chapter that I need to harvest in order to feed the hunger deep down in my soul that requires me to try at least, to connect with real people who really fought in the war. Even though they are all long dead. And even though I will never ever get closer to them than my soaring but limited imagination will allow.

Deviney though, he sort of flips me the bird from his unknown grave. His story, the more I uncover it, is one that I couldn’t even write as fiction if I wanted to because, as you’ll come to understand: I would have to fear people’s reaction.

I mean, their disbelief once they got through to the end of this tale, it would have to be expected.

_____

Dash-fire: a 19th Century slang term referring to vigor, manliness.

_____

You know, each and every one of our individual pasts are so worth discovering. All of our lives- before we were even alive- were already being lived in a sense, by the kind of characters many of us would never ever imagine we are related to. There are, I promise you, many people in your family past that you have little or no idea about, but who will blow your little modern mind if you do the work. Seek them out.

Pride, shame, you will know it all because it’s all there. Some of your ancestors were seriously fucked up and some of them were seriously cool. I kid you not.

So this multi-part/ roundabout/ meandering/ part memoir/ part bio-dive into the life and times of one my wife’s Great Grandfathers (and into the lives of Arle and me as a result) is something I’ve been wanting to write for a long time now. And even though here I am finally taking the plunge (having forced myself to start telling it before I get hit by a fucking train or something), I still need you to know that I am feeling super self-conscious about it. Because this guy, the things that ended up happening to him (and because of him at times throughout his life) it all has come to matter to me. Like, a lot. And because I feel connected to him somehow and because I feel like I would have liked him in real life even if he was a giant pain in the ass, I suspect that he deserves a better tale told about him than I feel like I can write.

But whatever. I’m the one that wants the gig. And I’m going to give it hell, too. So here I go. And here we go, if you want it.

And I think that you do.

Deviney is going to jail, y’all.

More than once.

And he is going to bite his own tongue in a most spectacular way.

And he’s going to be in the New York Times at one point and the whole damn country is going to be talking about him.

And he is going to be accused of murder.

And he is going to fight some more in the Civil War.

And he is going to tell the Civil War to kiss his little country ass, too.

More than once.

And it’s all kind of seeming to me as if he knew that someday: somebody called Thunder Pie would find him and drag him out of his dark unmarked grave and chuck him up on your desk or your kitchen table just so you, dear reader, could decide for your own damn self if he wasn’t the most badass American son-of-a-bitch that you ever heard of.

==========================================================================

==========================================================================

Maturity entails a readiness, painful and wrenching though it may be, to look squarely into the long dark places, into the fearsome shadows. In this act of ancestral remembrance and acceptance may be found a light by which to see our children safely home.

- Carl Sagan

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

***LATEST NEWS FROM THE FRONT!! LINCOLN’S BOYS DO GOOD!***

READ ‘THE DASH-FIRE DAYS OF PRIVATE DEVINEY (Part II)’ COMING NEXT WEEK!!***TREMENDOUS TALE OF LEGENDARY LIFE! ACTION! ADVENTURE! CRIME! WAR!

DON’ T MISS IT!! PAID SUBSCRIBERS ONLY!

==========================================================================

Hey there. I hope you really enjoyed this FREE essay. You want to read Part II???!! Of course you do. Then please support my writing and become a Thunder Pie weekly reader! It’s only $10 a month or $120 a year for 4 original essays a month, every Friday morning at 9am. That is a goddamn good deal if you think about it. Lots of original, thought-provoking content coming your way every single week! And by the way, if you are feeling excited by my work and feeling generous today and want to pay a little more… YOU CAN DO THAT! Custom subscription fee is totally available (above $120).

Thank you to anyone and everyone who reads and supports my writing.

Love/Serge

==========================================================================

All Photographs: by Alexander Gardner (Library of Congress) EXCEPT 125th Pa at Dunker Church (from 125th Pennsylvania Regimental History).

Edited by Arle Bielanko.

Email: sergebielanko@gmail.com

PLEASE visit my wife Arle’s Etsy shop, gnarleART for cool unique holiday gifts. It’s not too early to start shopping and your financial support of our art helps our family so much. Thank you!

Also subscribe for FREE to Letter to You by Arle Bielanko

==========================================================================

Oh, wow, I could not read this one fast enough wanting to know where this tale was going to go. Great writing, intriguing subject, and a personal connection. Awesome. I get the yearning to know these Civil War ancestors. I’ve got a few of my own, including a great-great who served on an ironclad battleship & survived the Battle of Charleston. You’ve crafted a vivid picture of Antietam. I visited there one foggy, rainy day & felt like hallowed ground. Your writing is so strong in this one. Looking forward to the next installment.

Man, it’s such a joy to follow you on your personal journey here, in your Friday essays. Your Civil War fascination reels us in. Your enthusiasm and wonder at it all becomes, for us, compelling. And the details you see and portray, the pictures you paint with your words, become something living and immediate. Already looking forward to Part 2, to hearing the next chapter. Have a good week, Serge.