A prison taint was on everything there. The imprisoned air, the imprisoned light, the imprisoned damps, the imprisoned men, were all deteriorated by confinement.

-Charles Dickens, ‘Little Dorrit’

Sitting there in his rattling irons, on a winter train headed straight away from everything he had ever known, the world was sliding by, freedom slipping away with every passing mile. Farms like the ones he’d wandered by and worked on all his young life so far, they came up into his vision for just a moment or two before they slid behind the barreling train, into the void of the world he could no longer enter. Patches of dead weeds standing tall at the corners of old bank barns, he would have ignored them to no end not long ago. But now they seemed angelic and beautiful and he craved to just hop off this damn train right now, even as it moved along at a good clip, just to tumble down into these foreign fields and pick himself up and go to sit there in the random nature, in a stranger’s weeds, as a show of remorse. As a signal that he was sorry for the crime. Or for getting caught, at least.

Kids throwing snowballs at the passing train, he’d see them through the dirty glass of the windows, out there laughing in the slate afternoon. Their arms bent down to their knees, frozen in position as their powdery artillery shells moved from their free mittens through the free air towards the free train itself/ some slashing/ some arcing/ some seemingly stopped in the sky for an instant or two before it began its descent back down towards the free land and the free train and the unfree people in it’s path. Prisoners, onetwotreefourfive, in the window seats near the guards with the rifles, they would have watched as the free snowballs hit that free glass with soft force/ a kind of thud-thud-thudthud-thud/ like the canons in the war of the years to come would sound to him. Someday.

County after county, town after town, river after stream and stream after river, a train moves a man from somewhere to somewhere else and depending on the timbre of the journey, on the reason for traveling, it can be either an uplifting journey primed by the excitement of a coming unknown/ or it can be a dreadful, horrifying thing/ moving you ever closer to a dead body of a loved one/ or the words of an unexpected goodbye/ or, as in our case here, closer/ ever closer/ to an impenetrable fortress of punishment. To a kind of un-freeing that has always been, up until now, simply unimaginable.

Miles from his country home then, as the afternoon sun began to sink into the lazy gauze of a dying day, the looming skyline of Philadelphia must have appeared like a fantastical kingdom in the eyes of the 21-year-old Deviney.

It was early January, 1859, and the city was surely ashen and smoky and unwelcoming. After all, everything that awaited my wife’s great 3x grandfather that day was steeped in mystery and fear and shrouded in regret.

The lad, as it goes, was headed to prison. Far, far from home: in a city the likes of which he had never even tried to imagine, let alone laid eyes upon. Mid-winter January afternoons on the eastern seaboard historically has me betting that the old town was frigid and dank that day he arrived. True, true, there are no guarantees, of course. Unable to find any official weather reports for that exact period, I’m basing a lot on nothin’ at all/ leaning hard into speculation based on what hardly registers as true history anymore: my own personal experience.

Still, I’m not totally without merit here. I mean, I have known some January days in that city in my time. More than a few, quite frankly. Most of them have been wickedly cruel, with little rest from slamming train-like winds into the faces of the people who turn certain corners onto certain avenues when certain gusts are being born out by the Delaware River in order to invade and maraud with no quarter upon every cursing hunched-over street walker it can find.

And so it goes that, here, in my imagined history of a true history, I make it cold as hell for the country boy the first moments he steps off the train. In shackles, perhaps/ in cuffs for certain. He’d been tried and convicted of larceny not long before. And true to the manner of a freshly rested court, I suppose, his post-holiday sentencing, in the days just after Christmas and New Years, had found him sentenced in Perry County on the 5th of January and quickly shipped off to Philadelphia. To Eastern State Penitentiary. A stranger in a strange land if there ever was one.

He must have been scared as hell.

And he must have been doing everything in his power to hide that fact from everyone.

____

_____

Opportunity makes a thief. -Francis Bacon

_____

Once, on a street in London, where the theaters draw thousands of tourists from all over the world/ bus loads/ train loads/ buckets from the sky tipping over and out rushes a rambling wave of humanity/ people with money/ people with no idea where they are except for the thrill of realizing- from a height above themselves on those bustling busy streets- that they are in London/ grand old London/ once, I was walking with a young lady/ sifting though the throngs/ trying not to lose my companion in the jam of the incessant ocean of faces and voices and shoulders touching/ arms rubbing/ when I felt my wallet go.

It had been in my back right pants pocket but then it wasn’t anymore and somehow I understood that in the moment it was happening. This isn’t often the case, I know, when an American like myself is drifting unmoored through the London theatre district masses. We, as a rule, never realize until later/ when we go to pay for a few pints in a pub or for a chintzy dish with the Queen’s face on it or for a taxi at the end of a night/ that our wallets are, quite rudely, missing.

Yet on this particular afternoon, I beat the system and felt it go and swiftly I sprung into action. But what happens in odd strange moments like these is that time slows down and you begin to wonder what you are about to run into on the distinct other side of this spinning around you have committed yourself to, unconsciously, I’d say. It’s all reaction, these things, you know? There is very little courage or cunning or intelligence at play at all, I would say.

Hell, halfway back into my wild move to confront a pickpocket, I also began to envision, quite clearly and with much intense detail, the slender silvery blade of such a small but useful knife, as it reflected the excitement of these lanes with local neon sparking off it’s surface/ like a masterful painting that captures the allure and the danger of big city movement/ in the very instants before that same blade thrusts slowly and deliberately into my belly/ like a pin into a potato/ like a finger into a pudding/ and sliced me wide open so that my guts/ my heaving grey bucket of goosenecks in their juices all slipped out of my shirt and onto the sidewalk into a heap rising up from a puddle where a thousand people would quietly cease their momentum to stand in fascinated awe: watching me die on an autumn afternoon as The Producers crowd was being let out/ heading to their early dinners/ chit-chatting and thirsty and ready for some wine.

Who can blame them? Any of them? Not me. No way.

And yet, upon reaching my destination, I observed no knife and no criminal and nothing I had been expecting. But rather, in the place of what I thought I would find there stood a very frail looking creature of which, even to this day, I am uncertain about as far as the sex goes. They may have been a boy, or they may have been a girl. They may have even been a man or a woman, but in that case they would have been quite unusual as far as that goes. Either way, I had them by the arm now and they were squealing/ begging me to let them go/ and no one else was clocking any of this as I slammed the thief up against the painted door of a closed shop and began to feel how much stronger I was than them and how extremely unexpected any of this was to me.

My wallet reappeared and I felt satisfaction, warm like whiskey or wide awake pissing your pants. I had my hand on his/her throat and I was glaring deeply into their eyes and their voice was high-pitched and I could tell they were scared, just like I was scared/ our lives intersecting on this insanely busy road at an insanely busy time of the day/ and I remember thinking how much it would have been a disaster for me if my wallet had gone missing and how much I felt like I was dreaming with my wallet in one hand and my thief in the other as I searched my mind for the punishment/ for the sentence/ for the thing that had to happen at this juncture which I hadn’t asked for or deserved whatsoever.

Then I recall, with great clarity, the release. Much as you might release a magnificent trout, so wild and free, and yet so threatened by the overwhelming sense of imminent death/ the toxic inebriation/ the fuzzy vision and the slamming heart that should and does come with being certain that you are about to die at the hands of another/ I released my grip and the thief’s eyes they lit up/ and my hearing came roaring back from the muffled tunnels it had gone down in.

I heard the streets again as I watched my thief take one step, then two steps, then a third step back the way we had both just come, before disappearing into the river of people, never to be seen by me again.

The thief. In their eyes I saw a person I have never forgotten. A weak bodied urchin grappling to survive. I doubt David Deviney was the same kind of thief. I doubt he was cut from the same kind of cloth that my own Londonish Charles Dickens-y downtrodden punk’s life had been. But also, I don’t know.

There are so many things that we never know about the people that try to take shit away from us so that it can be theirs. We all want to blame it on liquor or drugs or shiftlessness, but I’m not so sure.

Being a thief is an old, old way of living.

Being a thief, stealing out in the country or down in the city, it’s an ancient style of rolling through your days. Of surviving. And it isn’t easy. But some people are good at it. And they say you should do what you love too, you know?

Anyways.

I don’t like straight-up thieves.

But I don’t not like them anymore either.

____

____

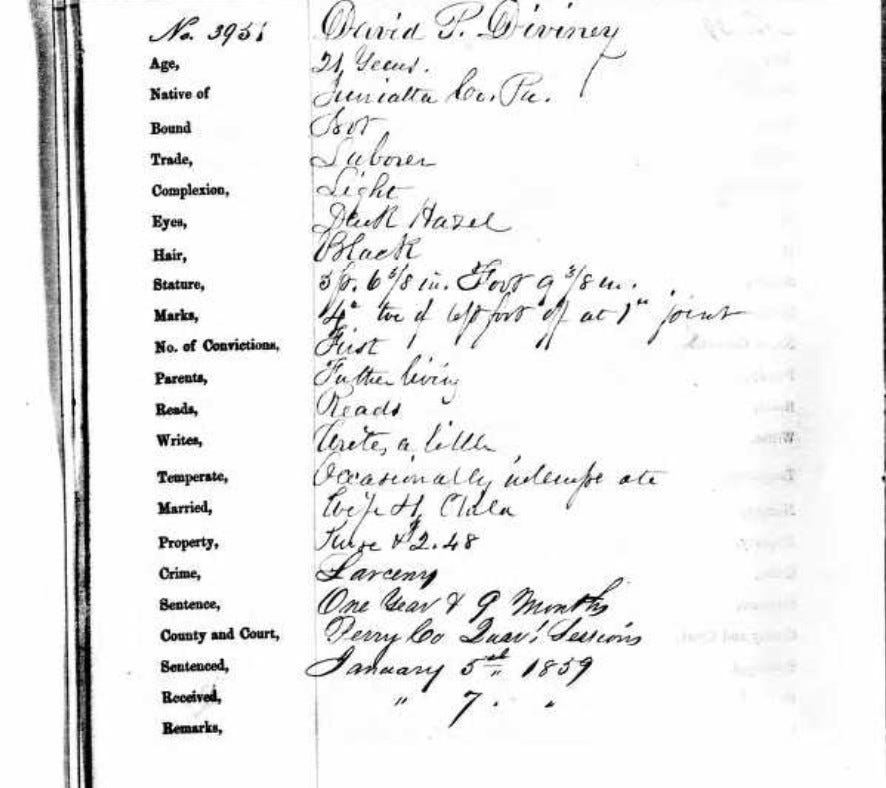

Records I found not long ago, they show that the new prisoner, Deviney, arrived just a few days after his guilty verdict had been announced. In what they call the Convict Reception Records from early January, 1859, someone at Eastern State Penitentiary in Philadelphia had written a short description of our inmate.

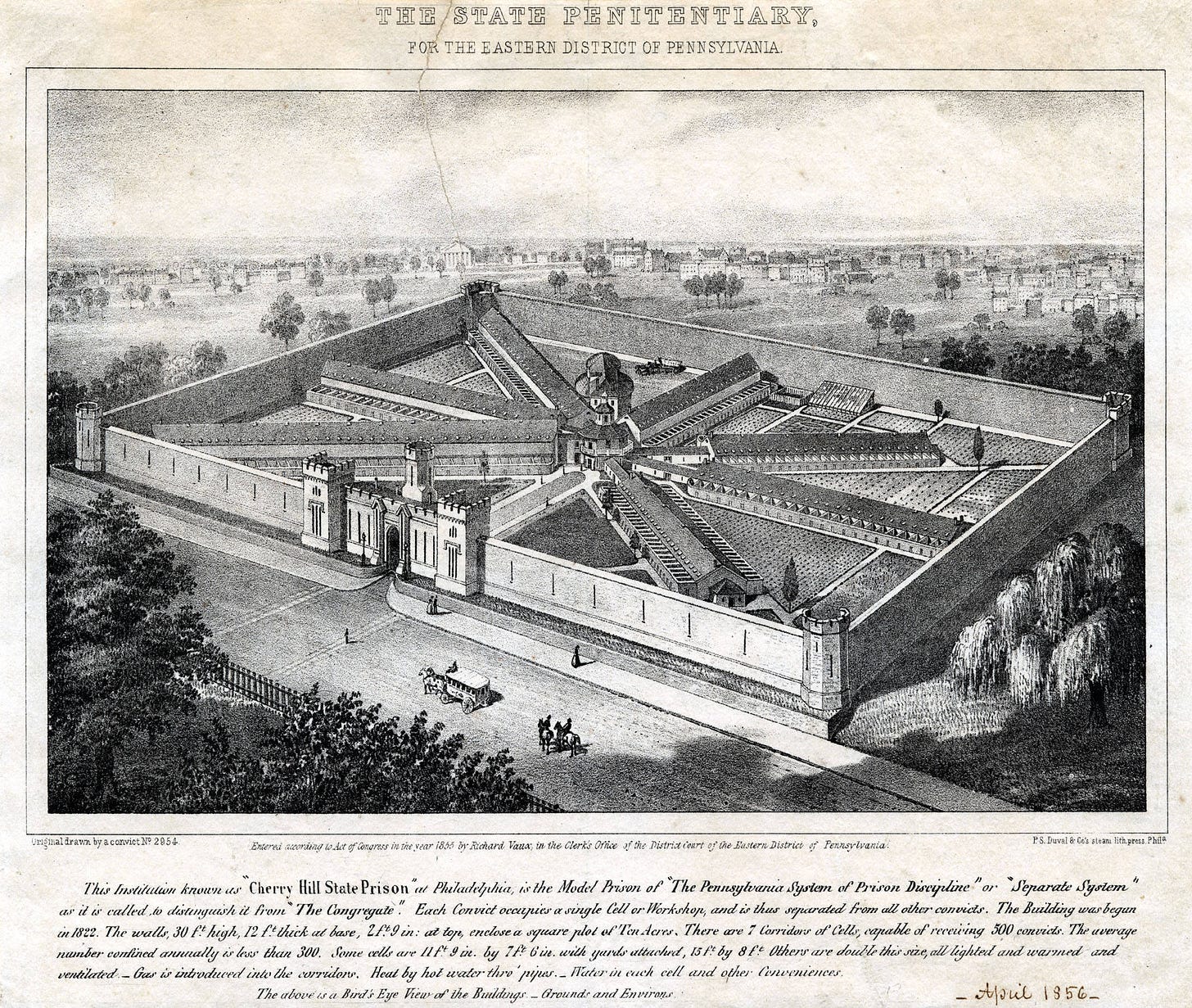

He was, according to the text, 21 years old the day he walked into the harrowing fortress/ old enough to have probably heard about this prison/ unconcern with the fantastical notion that he would ever even lay eyes on the place, let alone ever live inside it’s towering walls. The penitentiary was laid out like an octopus in a private garden/ sprawled/ seven separate long sections like legs all meeting in a body hall in the center. It was merely 30 years old at that point in time, but it’s reputation as the first-of-its-kind anywhere in the world had made ripples far and wide. It had been trumpeted as both an architectural wonder and a groundbreaking reformatory, inspired by the Pennsylvania Quakers, who believed that modern prisoners would be better served by spending their time in more spacious cells that they inhabited alone. Later this concept would bring protests from some (including the one and only Charles Dickens, after he visited in 1842) who deemed that this so-called version of ‘solitary confinement’ was inhumane. Yet, some historians have suggested that, unlike what we often associate solitary confinement with today, Eastern State prisoners, although bunking alone for much of the institution’s history, also had quite a bit of time outside of their cells for meals and recreation outdoors and such.

Either way, I suppose it doesn’t make all that much difference. Arle’s ancestor was checking in and it wasn’t likely going to be great… or even good… or even okay. This was, after all, prison. And he was there for stealing something/ I have no idea what. I did find records from the previous year that showed he was seriously behind on paying some of his taxes, but I know it wasn’t that transgression that he was jailed for. It does, however, possibly indicate to us that he was not doing all that well financially. And that would likely help us make more sense of why he ended up stealing something of significance.

Standing just 5-and-a-half-feet tall with black hair and “dark hazel” eyes, the in-taker at the penitentiary made some more unique notes concerning Deviney’s appearance as well.

He could read, it was noted. But he could only write “a little.” And this was his first criminal conviction yet his sentence was a fairly harsh one. 1 year and 9 months. That would mean, if he indeed served the entire sentence, that he would be released around September of 1860. Which, we should note, would have been about 6 or 7 months prior to the start of the Civil War.

In other words, Deviney was locked up while out in the world the United States of America was moving closer and closer to breaking apart. It’s likely, then, that he would have been exposed to different outlooks and opinions on the politics of the time while incarcerated. Men from his neck of the woods tended to be Democrats (remember that the Dems of the 1860’s were essentially the Reps of today), and there were no doubt ‘complicated’ feelings about slavery and its expansion in the south central Pennsylvania hills and valleys that he called home. Yet, many, many young men from that region would choose to be soldiers for the Union in the years to come. Deviney included. So it remans intriguing as hell to try and dive into why exactly Civil War soldiers fought and died for the side they were on. I won’t hit it to hard here simply because I don’t have any firsthand accounts from our guy here. But, oh, if I did. Oh… if I only did.

Also, you should probably know that the young prisoner also was missing a big old chunk of his 4th toe on his left foot. One can only imagine how that happened, as no records exist of it. But I’m no proud historian here/ I’m fucking Thunder Pie! And so I’m going to take a few wild guesses based on what little I actually know about country life in the 1800’s.

Let’s see. Well, he could have whacked it with an axe, right? I mean, that would definitely take a good swipe of toe meat and bone clean off. Or he might have hit it with a sledge hammer or had it run over by a wagon or stomped by a horse or a mule too, huh? Any of that could have absolutely ended up with a perfectly healthy young dude having to go see a doctor when the swelling and bruising got unbearable only to be told:

I’m gonna need to take the front part of that mess off there, son. And I ain’t gonna tell you that it ain’t gonna hurt but I will offer you this rag to chomp down on and this corn liquor to swallow to help take the edge off of what’s coming.

I wonder if he limped a little? Probably not. Fact is, I’m guessing that his missing toe part never really affected him much, especially since he will later be in the army and there’s never any mention of it as a disability or anything. Still, he’s lucky, I figure. Back then taking a toe off could have ended with infection and a bad, bad scene.

Other than that, the notes made upon his entering Eastern State Penitentiary don’t reveal too much. At least not on the surface of things, I guess. He is listed as only having a father living, so his mom must have already passed on.

And it says he was married already and that they had one child so far. Which must affect a man of his age, don’t you think? 21 and sent to the big city penitentiary from his rural home, forced to leave behind a young wife and what must have been a very young child, if not a baby. How does a mind deal with that? How does a person reconcile with knowing that, on that January day when they enter into the cavernous, echoing halls of the largest penitentiary on earth, they won’t be going home for a long time?

Did they come to visit him? Were they allowed? Were they able to pull it off if they were allowed? I just don’t know. Time has pushed me away from figuring all of this out so far.

But who knows. I won’t stop looking.

I won’t stop digging.

Truth be told: I can’t.

____

____

The records list ‘David Diviney’ as having $2.48 with him on the the day he reported to serve out his sentence.

That would be $88.49 today.

I wonder if he got it back when he was released? And if so, I wonder what he spent it on? A train home? A steak dinner in a tavern? Flowers for his wife? A doll for his daughter?

No one knows or ever will.

____

____

Around this time of year, the prison, void of prisoners for many moons now, is still quite busy. Although it’s been years since it housed any inmates, Eastern State Penitentiary still lives on as a living museum where you can walk into and amongst the standing ruins of the legendary place itself.

Al Capone was there at one time.

So were many female inmates.

So were some Confederates captured in the war.

Nowadays you can go to a Halloween haunted attraction there. It costs a fair amount but they say it’s really worth it. I believe that. I fucking love those things. I love to be scared inside old buildings where things once really happened. Pennhurst Asylum in SE Pennsylvania is like that. And so I suspect that ESP is the same kind of wonderful.

And yet, it’s easy to forget, even at times when you are literally shitting your own pants because you are SO FRIGHTENED, that a place like the penitentiary we are talking about, it was a sad, awful place for a lot of human beings. Sure, we can argue that many of them deserved to be there, I don’t dispute that, but I have come to grow fond of this David Deviney character. And even though he’s not officially my blood/ I don’t give a goddamn. I’m adopting him alongside my wife’s natural ties to him. I’m adopting him in my own way/ even if I don’t know what that really means yet. I’m taking him on because I want to. Because I need to. Because I connect with him somehow when I imagine him living his life.

Hunting rabbits in the fields. Fishing in a dirty stream. Walking down spring hillsides with a piece of rope and a basket of bread. Swimming in a tiny creek. Talking to his wife on the porch of a small dilapidated house. Holding his child. Watching his children.

Looking through the smoke of battle.

Stealing six of his neighbor’s sheep in the middle of the night.

Standing there naked in the cold caverns of the prison.

Being told not to move. Being given some prison clothes. Being led to his cell. Sitting there in the stony morning light, staring at a spider on the wall, on a street where I would someday walk. In a prison where his great great great granddaughter would someday walk. In a city where his great grandkids would all someday walk.

Smoking a pipe outside a shop.

Hollering at his son on the mountainside.

Laying in his tent, holding the letter.

Daydreaming of some impossible afternoon when he would no longer be around for any of this.

::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

The Dash-Fire Days of Private Deviney (Part III) coming soon.

Thanks for reading my work / supporting my art. I am really really grateful. -Serge

************************************************************************************************************

Read more about Philadelphia’s legendary Eastern State Penitentiary here.

Edited by Arle Bielanko.

Email: sergebielanko@gmail.com

Photos: TOP and 2nd from lifted from Eastern State Penitentiary. Last photo from Ancestry.com. Other photos stolen outright from the internet. By a thief of sorts, I guess.

PLEASE visit my wife Arle’s Etsy shop, gnarleART for cool unique holiday gifts. It’s not too early to start shopping and your financial support of our art helps our family so much. Thanks.

Subscribe for FREE to Letter to You by Arle Bielanko

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Freedom is what you do with what's been done to you. -Jean-Paul Sartre

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Man, this is some damn fine writing. Compelling. I’m not big on the Civil War, but I do dig tales of how everyday life was once upon a time. The Americana of it. How our cities used to be nothing more than big towns. You paint such wonderfully vivid pictures. I was sitting right there on that train, looking out in the countryside. Thanks again for doing this. For sharing your words. Already looking forward to part III.

Great continuation

from part one! I really like the switch from Deviney’s story in the past to your own experience with a thief in the present. Makes the exploration of thievery more relevant. I find this tale fascinating as I am obsessed with trying to find out personal details about my Civil War era ancestors. I’m really digging this piece as installments. Looking forward to the next one. Good work!